The Invisibles

toward a phenomenology of the spirits

Originally published in The Handbook of Contemporary Animism, 2013.

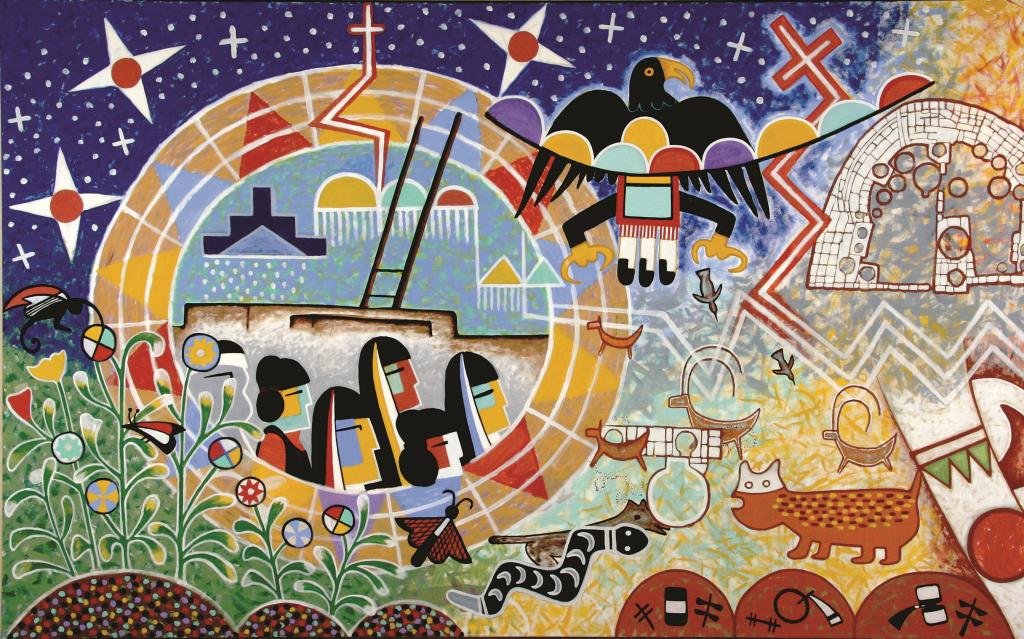

Michael Kabotie and Delbridge Honanie, Journey of the Human Spirit – The Emergence (Panel 1).

To live is to dance with an unknown partner whose steps we can never wholly predict, to improvise within a field of forces whose shifting qualities we may feel as they play across our skin, or as they pulse between our cells, yet whose ultimate nature we can never grasp or possess in thought. To affirm our own animal existence, and so to awaken inside the world, is to renounce the pretension of a view from outside that might some day finally fathom and figure every aspect of the world’s workings. It is to acknowledge the horizon of uncertainty that surrounds any instance of knowledge, to accept that our life is at every point nourished and sustained by the mysterious.

❖❖❖

If we really are corporeally embedded in the cosmos we see and sense around us, carnally situated in the midst of this earthly plenum, than we encounter the real only from within the depths of itself, and hence each aspect that we meet hides other aspects behind it. Sure, there are many facets or forces of the world that we can name– sun, soil and cliff, bear and bird, full moon and sickle moon, cloud, rain, river. Yet the very presence of these beings in the same field that we ourselves inhabit entails that there are aspects of each that we do not see; every visible facet of the world speaks to us of dimensions that are not visible.

It is not necessary to imagine other scales of existence– microscopic or sub-microscopic– in order to notice the world’s invisibility. Nor is it necessary to conjure immaterial or supernatural dimensions. It is enough, simply, to attend to the sensuous landscape that materially surrounds you, and to the very ordinary presences that populate that landscape. Consider, for example, the unseen character of that which is hidden behind the things that you do see. Each opaque entity occludes the things behind it, and each has its own other side that is concealed from our eyes at this moment. We may alter our position in order to glimpse that other side– but now different facets have hidden themselves, and presences that we saw clearly a moment earlier have now vanished, eclipsed by those in front of them. Wherever we move, and however we contort ourselves, we cannot dispel this strange invisibility of the visible world, the way it hides behind itself, withdrawing from our gaze. In the most close and intimate sense, we encounter this curious concealment in the unseen nature of the back of our own body; in the grandest sense we feel it in the way that the wide horizon of the visible landscape steadily hides, or holds in abeyance, all those lands that lie beyond it.

Yet there is another very basic mode of concealment that lends its mystery to the visible world: that which is hidden inside each visible thing. The inside of the many buildings we often pass on our way to school, the woody interior of a young maple tree, the interior density of a stone or a mountain, the internal physiology of a snake whom we’ve just disturbed, slithering off into the grass– almost all the visible presences that surround us bear a depth that remains hidden to us, an inner depth we cannot see. We experience this second form of invisibility, most intimately, as the concealment of our own bodily interior. Certainly we may sometimes imagine this interior, envisioning the inside of our body according to images that we’ve seen in our anatomy textbooks. Yet there is a sense of spaciousness, and light, in these conjured images that is contrary to the obviously dark and tightly packed nature of one’s real interior, of which we have no visible experience. Only the surgeon (and the subsistence hunter, who regularly skins and butchers his prey for food) catches a furtive glimpse of this dark interior that nevertheless remains, while we’re alive, almost wholly hidden from view.

In the most public sense, this second mode of invisibility is experienced in the hidden, or unseen, nature of whatever exists under the ground. Here too, while archaeologists may dig down beneath the topsoil in hopes of uncovering traces of prior cultures, and while geologists have learned to decipher the various strata of rock rendered visible by a highway cut or a river canyon, the vast bulk of what subsists at various depths beneath the ground is entirely hidden from our perception.

❖❖❖

Each of these modes of invisibility– that which is hidden behind the things that we see, and that which is hidden inside the things we see– lends a pervasive sense of enigma, and unknowableness, to the everyday world of our direct experience. An intuition that, despite all our accumulated knowledge regarding the workings of the world, we are in continual, felt relationship with unseen realms. It is a sense of the world’s mysteriousness– a feeling that is largely forgotten in the modern context, when many of us ponder the earthly world as though we were not entirely a part of this world, as though we were outside of nature, staring at a satellite image of the earth on our computer screens, or gazing at the “scenery” as though it were a flat backdrop. This earthly world loses its mystery when we presume to stand apart from it, when we consider it as a determinate set of objects to be measured and tallied, or as a stock of natural resources to be managed by humankind. Yet as soon as we return to the immediacy of the present moment, and hence to our ongoing, animal experience in the midst of this world, then the flatness dissolves, and the enigmatic depth of the world becomes apparent.

Indeed, the two modes of concealment that we’ve just noticed have everything to do with depth; in fact, they each reveal a unique meaning of the term “depth”. The hiddenness of that which lies behind visible things, and ultimately beyond the horizon of the visible landscape, is a function of horizontal depth, which photographers call “depth of field”. It is that deep dimension to which we allude whenever we speak of the relative closeness or distance of perceived things.

Meanwhile, the concealment of that which rests inside the visible bodies around us– within the tree trunk, and the stone, and ultimately within the solid earth itself, under the ground of the perceivable landscape– is also a matter of depth, in this case inward, vertical depth: that precipitous dimension that we allude to when we speak of the depth of a dark lake, or the local depth of the bedrock, or the yawning depth of an abyss.

Both of these depths– the enigmatic depth of the distances and the alluring depth of the abyss– become evident and operative only for a creature that is materially embedded in the landscape that he or she perceives, carnally situated in the midst of the sensuous. Each lends its unique mystery to the world, ensuring that there is a recalcitrant otherness to the things we perceive, a certain resistance of the world to our human desires and designs. Of course there are other unseen dimensions– the unseen character of sounds, for instance, or of smells, or even of thoughts. But while it is quite possible (even simple) to imagine a visible world that lacks these various dimensions– a field of visible things unaccompanied by sounds, or smells, or thoughts– it is impossible to imagine a visible field without the invisible dimensions that we’ve been discussing. They are entirely necessary to the world’s visibility.

❖❖❖

There remains, however, a third form of invisibility that is integral to the visible world, a third mode of concealment entirely necessary to the visual surroundings.

In concert with the unseen presence of what lies, at any moment, behind the visible things, as well as the hidden existence of that which dwells within those visible bodies, there is also the invisible presence of that which moves between the visible things– the unseen atmosphere, the air.

Itself invisible, the air is the medium through which we see all visible things. And here as well, this third dimension of invisibility corresponds to a particular aspect of depth. It is the third and most profound meaning of depth: the depth of immersion.

This is the most primordial sense of depth, a dimension to which we refer whenever we say that we are “in the depths” of something– wandering in the depths of a great sadness, or caught up in the depths of an all-consuming task– as thoroughly as fish are immersed in the sea. Or as thoroughly as our breathing bodies are immersed in, and permeated by, the unseen atmosphere of this world.

❖❖❖

The other side of things, the inside of things, and the medium between things: three aspects of depth, each of which corresponds to a unique form of invisibility that haunts the visible world. The secret character of that which lies under the ground; the unknown nature of that which waits beyond the horizon; and the mysteries unfolding within the invisible air itself.

For the human animal, there is no place, no region of the earth that is not triply haunted in this way. Yet the specific quality of these three enigmatic dimensions, and the precise manner in which they intersect and inform one another, is curiously different in each locale. It is this unique conjunction of invisibles, we might say, that defines the genius loci, the particular power of any place.

❖❖❖

It is obvious, then, that from the perspective of our gazing bodies, the sensuous world is riddled with uncertainty. Our most immediate experience of the earth around us brings at the same time a felt awareness of obscure and ambiguous realms. Indeed, the very visibility of our world implies, from the first, an array of unseen dimensions whose reality we can sense yet whose enigmatic invisibility simply cannot be overcome.

A feel for the mysterious and the unseen, in other words, is entirely proper to our experience of the material surroundings. Invisibility is not, at first, an attribute of some immaterial or supernatural domain beyond the sensuous, but is integral to our encounter with visible nature itself. While there are, to be sure, many shapely and richly coloured things that we can point to or specify with some precision, the relations between these visible things– the ways that they influence one another, and influence us– remain hidden. We know that plants at a distance from one another nevertheless exchange pollen between themselves, and that they attract insects and other pollinators who approach them from afar– yet the precise vector of these exchanges, or the atmospheric gradients that effect such distant attractions, remain unseen. The abundance of trees in certain regions seems to affect the prevalence and density of the visible clouds that sometimes gather above them, yet the operative tensions and flows that enact this influence remain invisible. So, too, the rains that fall from those clouds upon the ground seem to deepen the green and leafing life of those trees, yet the paths taken by rain once it vanishes into the earth– the precise pathways whereby that water is first drawn into a lattice of rootlets and then up through the thicker roots into the trunk, and finally distributed among those many leaves– are concealed from our blinking eyes. Countless flows, torsions and tensions structure and transform the breathing terrain we inhabit, yet the vast majority of those flows are hidden from our direct apprehension.

Nonetheless, by virtue of our carnal enmeshment in the same field as those trees and those clouds, we can sometimes intuit or feel the pull of these unfoldings as they subtly play across our flesh. Other unseen flows can be sensed only by extending our bodily imagination outward, into the voluminous depths of the living landscape.

❖❖❖

Yet while such invisible forces and torsions may make themselves felt, we almost never perceive them directly– and hence we cannot delineate them with any precision, can hardly define or even describe them without violating their ephemeral quality, without falsifying their constitutive invisibility. Although we sense that such enigmatic unfoldings make up a large part of our world, we can allude to them only obliquely, indirectly, wielding figures of speech that are purposely– even playfully– ambiguous.

Such, for instance, are the multiple “intelligences”, “powers” and “spirits” that populate the oral discourse of indigenous peoples throughout the world. Every community that lives in close and intimate contact with undomesticated nature– whether hunters and gatherers, or subsistence horticulturalists– acknowledges the myriad energies that move in the invisible depths of the sensuous, honouring these powers with regular gestures of offering in return for the steady provision of earthly sustenance. Cultures whose reliance upon the animate earth is not, as yet, mediated by a crowd of technologies cannot help but experience the seasonal nourishments upon which they depend as gifts that offer themselves from the unseen heart of the mysterious. The plants we consume for food quietly emerge from the dark depths underground; the bison or caribou arrive each year from distances hidden beyond the horizon; the water that quenches our throats is replenished by clouds that somehow gather and materialize from the invisible depths of the medium.

Only mistakenly, then, do we interpret the unseen “spirits” honoured by indigenous, oral peoples as wholly disembodied, supernatural entities– immaterial phantasms conjured by a naïve and primitive imagination. Are the streams and vortices in the invisible air disembodied? Is there no materiality to these jostling surges and subsidences that compose the fluid expanse in which we’re immersed? Or to an unseen cloud of lichen spores riding those currents like a transparent silken cloth? Is the hidden sap rising within the trunk of a Ponderosa pine, or the infection spreading through the body of a young elk, supernatural? The “spirits” or “invisibles” spoken of by oral, indigenous peoples are not aphysical beings, but are a way of acknowledging the myriad dimensions of the sensuous that we cannot see at any moment– a way of honouring the manifold invisibilities moving within the visible landscape– and of keeping oneself and one’s culture awake to such unseen and ungraspable aspects of the real. They are a way of holding our senses open to what is necessarily obscured from view, a way of staying in felt relation to the unseen waters that sustain us, to the invisible tides in which we are immersed. As such, an acknowledgment of “the spirits” is part of the practice of humility. It is a practice necessary to avoid endangering one’s community– a simple and parsimonious way of remembering our ongoing dependence upon powers we did not create, whose activities we cannot control.

❖❖❖

In truth, it is only we of the literate, technological West who tend to construe “the spirit” as something utterly insubstantial, entirely beyond all sensory ken. It is only literate, Christian civilization that assumes the spirit is something entirely outside of the world that our breathing bodies inhabit. The word “spirit”, of course, derives from the Latin spiritus– a word that originally signified “wind” and “breath”– an ancestry it plainly shares with the English term “respiration”. By severing the term “spirit” from its very palpable, earthly provenance as the wind, alphabetic civilization transformed a mystery that was once simply invisible into a mystery that was wholly intangible– incapable of being felt by any of the bodily senses. By thus pushing the spirit out of the sensuous sphere, civilization divested the material world of its enigmatic depths, of its distances and its concealments. Stripped of its constitutive strangeness, voided of its obscurities and invisibilities, the material world could now be construed as a pure presence, a pure object capable of being seen, at least in principle, all at once. Capable of being known, at least in principle, in its entirety– without any hindrances or ambiguities. And we, the pure knowers, no longer experienced material reality from within its own depths; we now hovered apart from the palpable world, surveying this grand object with the impartial gaze of a disembodied intelligence– a pure mind or subject without physical qualities or constraints.

Only when we pretend to look upon the world from this bodiless vantage does the world appear as a wholly determinate and defineable presence, capable of being known in its entirety. Whenever we speak of nature in strictly objective terms, whenever we consider the material world as a compilation of determinate events entirely susceptible to quantitative description, we tacitly lean upon this curious notion of nature as a sheer plenum that can be known from every angle all at once– a plenum from which we, the knowers, are necessarily absent. Sure, our animal bodies may be included within that measureable and mechanical nature, but our conscious, knowing selves are not. We float apart from that nature, pondering the material plenum from outside.

It has proved itself a very useful illusion, this view from outside the world. Yet it is now evident that by treating the material world as an object from which we ourselves are absent, we are rapidly wrecking the ability of the biosphere to support our human presence. The topsoils, forced to produce ever more abundantly, are rapidly becoming exhausted, depleted of nutrients. The waters, long a convenient dumpsite for our industrial wastes, have become toxic. The torn atmosphere no longer veils smooth-skinned creatures like us from the incoming fire of the sun. The earth shivers ever more rapidly into a fever, while numerous other species– whole styles of sensitivity and earthly sentience– tumble helter-skelter into the gaping maw of extinction. It will likely not be long before our own clever species follows them.

Unless, that is, we wake ourselves from the long delusion of our detachment from the bodily earth– to find ourselves included, once again, in the breathing body of the world. Unless we begin to engage the land around us as attentive participants within its vast life, letting our actions draw guidance from the other participants– the other beings– whose sentience is so richly entangled with ours. Unless we emerge from our technological cocoon, shaking our senses free from their stunned immobility, stretching open our eyes to receive the sun’s glint off the wing of a peregrine circling above the city buildings, and opening our ears past the play of words toward the voices of silence.

For it is not just our technological entrancements that hold us aloof from the earthborn world, but ways of speaking and thinking that have arisen in tandem with those technologies, and which now have an inertia all their own. How to hold our intelligence down here in the thick of things when our language keeps dragging us out of the sensuous, when our words and the way we wield them keep freezing the things, deadening their dynamism, closing them up within themselves as fixed and finished commodities?

❖❖❖

Each of us has our moments of startling sensorial clarity– moments when the evercycling surge of abstract thoughts dissolves into the liquid eloquence of a brook made swollen by new rainfall, its waters frothing and tumbling over the guttural stones. Yet we rarely hold ourselves in such animal alertness; as soon as we turn toward our friends and begin to talk, our tongue seems to tear our awareness out of the foam and flux of the present moment. As literate persons, we’re wedded to the protective fold of reflection, wherein our language loops recursively back upon itself– the speaking self dialoguing inwardly with its own words, verbal thoughts provoking and then playing off of other verbal thoughts, around and around, to the cool exclusion of the wind upon our skin.

If we wish to renew our solidarity with the more-than-human terrian, then we may need to think in some fresh ways. How, for instance, might a renewed awareness of this earthly world’s invisibility translate most easily into thought and speech?

❖❖❖

It rained long and hard last night. Walking in the old orchard this morning, stepping across bare patches of dirt between the trees, I look close and notice a small, delicate leaf emerging from under a clump, then peering still closer I notice another, abruptly realizing that the ground is full of the tiny green shoots pushing up from the dark earth. So many seeds must have been sleeping within the dry topsoil, waiting so patiently for the magic of rain! I grasp the thick branch of an apple tree and lean back against it. It bends, then flexes back, springing me back to my vertical stance. I reach toward a leafing twig from another branch and gently tug on one of its leaves. The branch arcs toward me for a moment, and then tugs back. I can feel the adamant life in the leaves, the limber muscle of sap-infused wood. As though merely to bend the branch of an apple tree is a simple experience of reciprocity, a casual meeting between two divergent lives.

Later, I hike up the hill behind the house, walking beneath cottonwoods and then picking my way among juniper and pinyon, then finally up among the tall Ponderosas and a small grove of aspens. Across from me is a south-facing hillside thick with juniper and pine, both the shorter-needled pinyons and the long-needled Ponderosas, a deep green blanket punctuated here and there with the brighter foliage of some low deciduous trees. I know well, from my readings, that deciduous leaves have cells on their surface that are sensitive to the entire spectrum of visible light, and I suspect that needles have the same gift. I learned the complex chemistry of photosynthesis back in high school, and studied it much more intently in college, suitably impressed by the elegant efficiency of the process. But still I wonder: what does it feel like to be so rooted in a place, sipping minerals through root filaments that extend themselves, by taste, through the dark density underground, while drinking the sunlight, by day, with your needles? What is the sensation of transmuting sunlight into matter? Surely, we don’t really believe that such a metamorphosis happens without any concomitant sensation– that there is no experience whatsoever accompanying this transformation!

It seems clear that leafing trees lack a central nervous system, and hence are probably far less centralized than we in their experiencing. Nonetheless, that sensations are not referred to a central experiencer does not negate the likelihood that sensations are being felt in the leaves themselves. Experience, for most plants, is simply a much more distributed and democratic affair than it is for more hierarchically organized entities like us.

We may wish to assume that a cottonwood tree is utterly void of sensation, and hence that a summer sunrise makes no impression within its flesh. We may convince ourselves that there is no feeling within its leaves that might distinguish an afternoon of steady overcast from an afternoon without clouds, no sensation at the tip of its roots when a drenching rain penetrates the soil, or within the woody sheath of the cambium as the sap rises within the trunk, and that indeed all the daily and seasonal shifts within a tree’s metabolism unfold according to a purely mechanical causality, without any need of sensation and indeed in a complete absence of impressions (in a blank, vacant expanse of mute materiality). But such a notion commits us, once again, to the belief that awareness originates outside of the body and the bodily earth.

For it implies that our own capacity for experience is a sudden arrival in the material field. It entails that our sentience cannot be the elaboration of a sensitivity already inherent in organic matter– a responsiveness already present, for instance, in the myriad microbial entities whose activities collectively enable much of the metabolism of plants and animals– and hence must be a power that abruptly breaks into bodily reality from elsewhere.

If, however, I allow that this wild-fluctuating sensibility I call “me” is born of this upright body as it dreams its way through the world– if I allow, for instance, that my sentience is supported by the air streaming in through my nostrils, and by the manifold sensibilities that move within me (by the keen responsiveness of the bacteria in my gut, and the skittishness of each bundled neuron within my spine)– then a new affinity with the sensuous world begins to blossom. For now the other bodies that I see around me, whether blackbirds or blades of grass, or the iridescent beetle currently crawling across my shirt, all give evidence of their own specific sentience. The emerald leaves dangling like wings from the near branch of an aspen attest by their very hue to a kind of ongoing enjoyment along the fluttering periphery of the tree– an exaltation of chlorophyll. As though one’s breathing lungs were flattened out and spread across the smooth surface of one’s skin, and the day’s warmth brought a tingling transmutation along that surface, one’s outermost membranes being ravished by the rays, from dawn until dusk.

Looking up, I notice the needled hillside across the valley now as a curving field of sensations– for my skin feels the variegated green of all those trees as a quiet ecstasy riding the hill. It is an ecstasy of which I myself regularly partake by receiving the radiance of that colour within my eyes, a gentle edge of pleasure that has always been there for me in the green hue of leaves and of needles– a subtle delectation in the sight of green, felt much more intensely whenever sunlight spills across the visible grasses or the leafing trees– but which I have become fully conscious of only now, a kind of empathy in the eyes. Just where is this empathic contact taking place? Am I slipping out through my eyes and plunging across the valley to meet and feel the pleasure in those needles? Is there some force pouring out from those branches and striding through the thickness of air to meet and join my body here where I stand staring? Somewhere between there and here (perhaps at every point between us), there is contact and a kind of blending. This simple instance of perception, this momentary meeting across the expanse of the valley, cannot help but be influenced by the mood of the medium between us, encouraged or obscured by the many happenings unfolding within that invisible depth– by its local turbulences and eddies, by condensations and warm updraughts and the cool, pellucid calms that briefly open or close within the unseen river of air as it rolls between my body and that breathing hillside.

Our perception of the things around us is everywhere mediated by such invisibles. The reciprocity between our body and the earth is enabled by a host of unseen yet subtly palpable presences, fluid and often fleeting powers whose close-by presence we may feel or whose influence we can intuit yet whose precise contours remain unknown to us. Felt presences whose lives sometimes mesh with or move through us so seamlessly that they cannot be rendered in thought, but only acknowledged. Or honoured with simple gestures of greeting, and sometimes of gratitude.

And so, if we wish to open our awareness to the actual place we inhabit, freeing our senses to perceive the terrestrial reality that so thoroughly enfolds us, it is likely that we will have to welcome the spirits back into our speaking.

❖❖❖

Whether we allude to them as spirits, or powers, or presences (or even– in keeping with local oral tradition– as gnomes, elves, fairy folk or other “invisibles”) it is only by addressing these unseen elementals that we begin to loosen our senses, waking minute sensitivities that have lain dormant for far too long. By allowing such enigmatic phenomena back into our discourse– acknowledging them neither as wholly objective entities nor as purely subjective experiences, but (like whiffs carried on the breeze) as ambiguous realities that move both around us and within us, and sometimes move through us– we rejuvenate the participatory sentience of our bodies. By speaking of the invisibles not as random ephemera, nor as determinate forces, but as mysterious and efficacious powers that are sometimes felt in our vicinity, we loosen our capacity for intuition and empathic discernment, unearthing a subtlety of sensation that has long been buried in the modern era.

And it is by means of such subtle sensations that the living land tunes our bodies, coaxing our communities and our cultures into a dynamic, dancing alignment with the breathing earth. The spirits are not intangible; they are not of another world. They are the way the local earth speaks when we step back inside this world.