ESSAYS

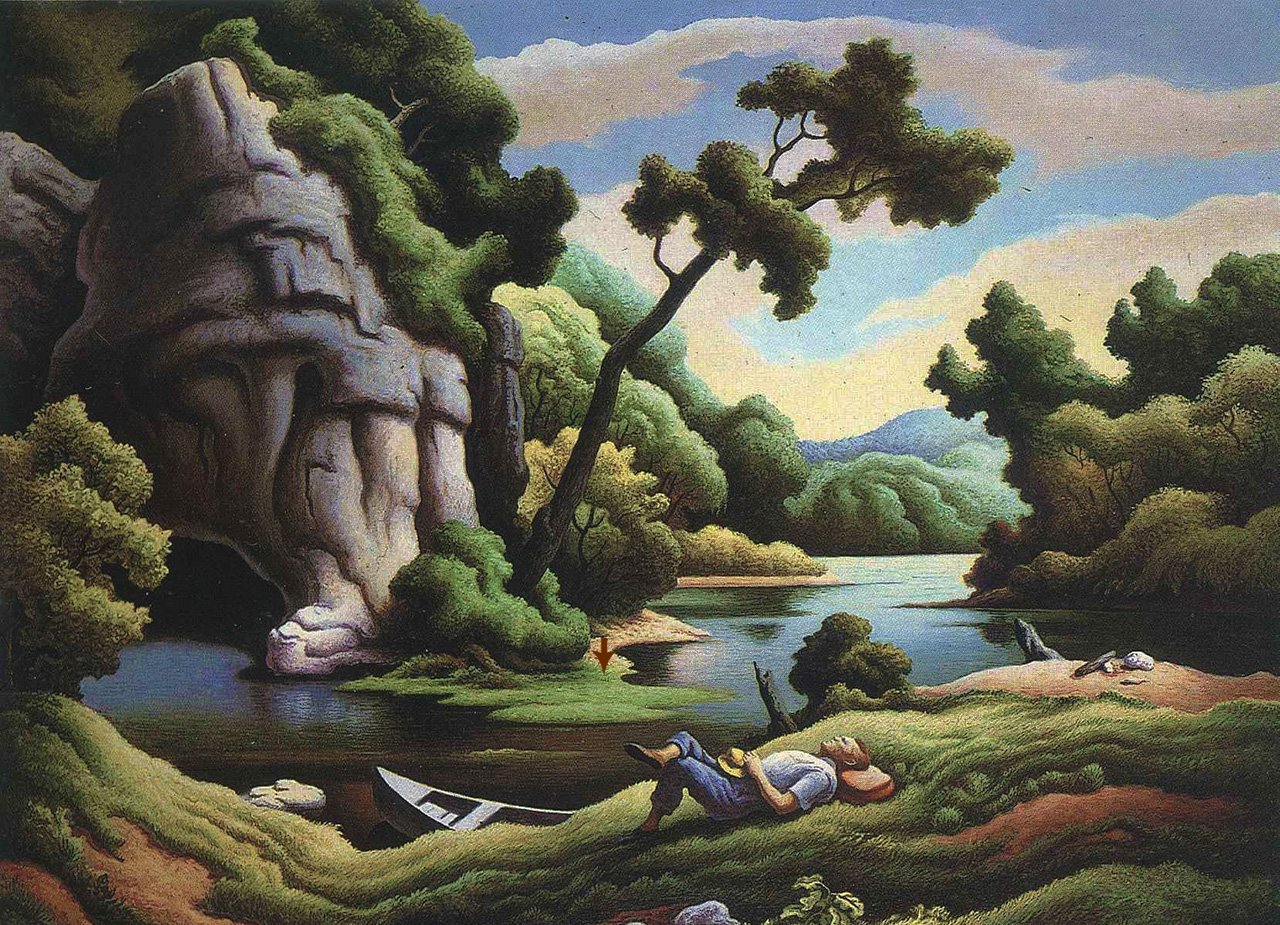

Thomas Hart Benton, Cave Spring

Earth in Eclipse

There is another world, but it is in this one.

— Paul Eluard

As a fresh millennium dawns around us, a new and vital skill is waiting to be born in the human organism, a new talent called for by the curious situation in which much of humankind now finds itself. We may call it the skill of “navigating between worlds.”

All Knowledge is Carnal Knowledge: A Correspondence

David Abram: Hi, David! Here I am at last. My sweetheart and I have been wandering through the American West, snooping around for a potential community, and although no place reached up through our feet and grabbed us, we’ve landed for a time in the high desert of northern New Mexico—in the midst of a mongrel community of activists I know fairly well from years spent living and loving in this dusty terrain before moving to Washington State three years ago. We had hoped that island realm would claim us, but the combined effects of Boeing, Microsoft, and the city of Seattle generally sprawling all around us, sprawling up into our noses and our ears, finally forced us to flee. We embarked on this most futile of quests in turn-of-the-millennium America: the quest for wildness—wildland and wild, earthy, close to the ground community. Slim pickin’s these days. Development everywhere, clearcuts even in the back of the backcountry, streams ravaged by effluent from abandoned mining operations. It’s not all hopeless: there’s still plenty mystery out in them thar hills, but I was mostly shocked by how the same all the towns are becoming. Ah well . . . I suppose Canada’s a decade or two behind the States, and if only we could get visas to live and work in Canada, we prob’ly be there in a flash.

David Abram interviewed by Derrick Jensen

Derrick Jensen: I’d like to start with two questions that might actually be one. They are: Is the natural world alive? And second, what is magic?

David Abram: Is there really anything that is not alive? Certainly we are alive, and if we assume that the natural world is in some sense not alive, it can only be because we think we’re not fully in it, and of it.

Actually, it’s difficult for me to conclude that any phenomenon I perceive is utterly inert and lifeless; or even to imagine anything that is not in some sense alive, that does not have its own spontaneity, its own openness, its own creativity, its own interior animation, its own pulse — although in the case of the ground, or this rock right here, its pulse may move a lot slower than yours or mine.

Now your other question: What is magic? In the deepest sense, magic is an experience. It’s the experience of finding oneself alive within a world that is itself alive. It is the experience of contact and communication between oneself and something that is profoundly different from oneself: a swallow, a frog, a spider weaving its web…

All-Species Representation at the Bioregional CONGRESS

Resolution From NABC II

We resolve that NABC III recognize four participants to represent the interests and perspective of our non-human cousins:

One for our four-legged and crawling cousins, One for those who swim in the waters, One for the winged beings, the birds of the air, and One very sensitive soul for all the plant people.

Other participants who wish to keep faith with other species are welcome; however, those four individuals formally recognized to act as all-species representatives will not participate in any other capacity during the time that they function as representatives. Their role in the Congress is partly one of deep stillness, of being profoundly awake, of keeping faith with those beings not otherwise present within the circles.

In the Depths of a Breathing Planet

By providing a new way of viewing our planet—one that connects with some of our oldest and most primordial intuitions regarding the animate Earth—Gaia theory ultimately alters our understanding of ourselves, transforming our sense of what it means to be human. For much of the modern era, earthly nature was spoken of as a complex yet mechanical clutch of processes, as a deeply entangled set of objects and objective happenings lacking any inherent life, or agency, of its own. Such a conceptual regime helped sustain the cool detachment that was generally deemed necessary to the furtherance of the natural sciences. Yet the thorough objectification of nature also served to underwrite the sense of human uniqueness that has permeated the modern era. As long as the Earth had no unitary life, no agency, no subjectivity of its own, then we humans could continue to ponder, analyze, and manipulate the natural world as though we were not a part of it; our own sentience and subjectivity seemed to render us outside observers of this curious pageant, overseers of nature rather than full participants in the biotic community. The thoroughgoing objectification of the Earth thus enabled the old, theological presumption—that the Earth was ours to subdue and exploit for our own, exclusively human, purposes—to survive and to flourish even in the modern, scientific era. Gaia theory, however, gradually undoes this age-old presumption.

Merleau-Ponty and the Voice of the Earth

Slowly, inexorably, members of our species are beginning to catch sight of a world that exists beyond the confines of our specific culture—beginning to recognize, that is, that our own personal, social, and political crises reflect a growing crisis in the biological matrix of life on the planet. The ecological crisis may be the result of a recent and collective perceptual disorder in our species, a unique form of myopia which it now forces us to correct. For many who have regained a genuine depth perception — recognizing their own embodiment as entirely internal to, and thus wholly dependent upon, the vaster body of the Earth — the only possible course of action is to begin planning and working on behalf of the ecological world which they now discern.

Animism, Perception, and Earthly Craft of the Magician

Although the term “animism” was originally coined in the nineteenth century to designate the mistaken projection of humanlike attributes — such as life, mind, intelligence — to nonhuman and ostensibly inanimate phenomena, it is clear that this first meaning was itself rooted in a misapprehension, by Western scholars, of the perceptual experience of indigenous, oral peoples. Twentieth-century research into the phenomenology of perception revealed that humans never directly experience any phenomenon as definitively inert or inanimate.